The Unexpected Champion

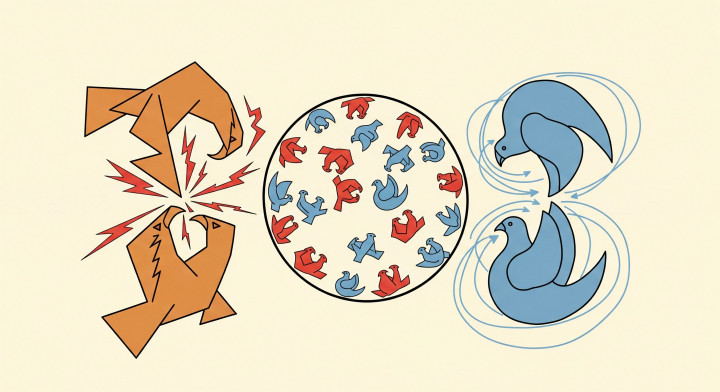

In the world of science, sometimes the most profound insights come from the simplest of experiments. In the early 1980s, at the dawn of the personal computing era, a political scientist named Robert Axelrod set up a digital arena to pit computer programs—each with its own "personality"—against each other in a classic game of strategy. The results were not just surprising; they were groundbreaking, offering a powerful new lens through which to view the evolution of cooperation itself.

Setting the Stage: The Dilemma of Trust

The experiment was built upon one of game theory's most famous puzzles: the Prisoner's Dilemma.

You're likely familiar with the classic setup: two partners in crime are arrested and held in separate cells, unable to communicate. The prosecutor offers each of them a deal, individually.

- If you betray your partner (defect) and they stay silent (cooperate), you go free, and they get a long sentence (e.g., 10 years).

- If you both stay silent (cooperate), you both get a short sentence (e.g., 1 year).

- If you both betray each other (defect), you both get a medium sentence (e.g., 5 years).

From a purely individualistic, rational perspective, defecting is always the best move. If your partner cooperates, you get the best outcome (freedom). If your partner defects, you avoid the worst outcome (being the sucker). The paradox is that when both players follow this "rational" logic, they both end up worse off than if they had trusted each other.

Axelrod was interested in what happens when this isn't a one-time encounter. He focused on the Iterated Prisoner's Dilemma (IPD), where the same two players face each other again and again. Suddenly, reputation and memory matter. The "shadow of the future" changes everything. Does cooperation stand a chance?

The Great Algorithm Tournament

To find the answer, Axelrod invited academics from various fields—economics, psychology, mathematics, and computer science—to submit a program that would play the Iterated Prisoner's Dilemma. Before introducing the digital contenders, however, it's essential to understand the rules of the game that would determine their success or failure.

Points Instead of Prison: Structuring the Tournament

To have strategies compete in a computer tournament, Axelrod had to translate the Prisoner's Dilemma into the language of bits and bytes. Instead of the abstract threat of prison years, he introduced a concrete, measurable system: points. The logic of the setup remained, but the perspective was flipped. The goal was no longer to minimize punishment but to maximize reward.

In each round, the two players (programs) could earn points. Their decision—to cooperate or defect—determined the payoff. The scoring matrix that formed the basis of the tournament looked like this:

- Mutual Cooperation: If both programs choose to cooperate, they both receive a nice, fair reward. Each gets 3 points. This is the reward for trust and collaboration.

- You Defect, They Cooperate: If you choose to defect while your opponent naively cooperates, you get the biggest prize, and they are left with nothing. You get 5 points (the Temptation payoff), and your opponent gets 0 (the Sucker's payoff).

- Mutual Defection: If you both choose the path of mistrust and defect, you each receive a minimal consolation prize, but you do far worse than if you had cooperated. You each get only 1 point. This is the punishment for mutual distrust.

This scoring system brilliantly preserves the tension of the original dilemma:

- The temptation is always there: No matter what your opponent does in a single round, it is always better for you to defect. If they cooperate, you get 5 points instead of 3. If they defect, you get 1 point instead of 0.

- The paradox remains: If both players follow this short-term "rational" logic, they each score 1 point per round. By contrast, if they had trusted each other, they could have each earned 3 points. The total gain for the pair from mutual defection (1+1=2) is far lower than from mutual cooperation (3+3=6).

And here's where it gets interesting. Since the tournament ran for 200 rounds, winning a single match (by pocketing the 5 points) could be a Pyrrhic victory. If a program built a reputation as a ruthless defector, other programs (capable of remembering past moves) would simply refuse to cooperate with it. This program would doom itself to long-term, back-and-forth defections, earning only 1 point per round.

The real challenge wasn't how to beat an opponent in a given round, but how to foster an environment where mutual cooperation (the 3-point outcome) could flourish. The key to success was not to knock out your opponent, but to build a long-term, fruitful partnership with them. With this setup, Axelrod made trust, reputation, and the weight of future consequences central to the competition.

Axelrod invited submissions from a wide range of experts. Each program was a strategy, a set of rules for deciding whether to cooperate or defect in a given round.

The entries ranged from the brilliantly complex to the deviously simple. Some were relentlessly nasty, always defecting. Others were purely altruistic, always cooperating. Many were highly sophisticated, using statistical analysis to predict their opponent's next move. These digital "personalities" were entered into a round-robin tournament. Each program played every other program (plus a clone of itself and a program that made random moves) for 200 rounds. The goal was not to "win" individual matches but to achieve the highest total score across the entire tournament.

The stage was set for a clash of digital titans. The expectation was that a complex, cunning strategy would prevail.

What happened next was remarkable.

The Winner: A Masterclass in Simplicity

When the digital dust settled, the victor was one of the simplest strategies submitted. Its name was Tit for Tat, and it was written by Anatol Rapoport, a mathematical psychologist.

Tit for Tat's logic was almost laughably simple:

- On the first move, cooperate.

- On every subsequent move, do what your opponent did on their previous move.

That's it. If the opponent cooperated, Tit for Tat cooperated. If they defected, Tit for Tat immediately defected back. It was a simple echo, a digital mirror. It held no grudges beyond the immediate last move and never tried to outsmart its opponent.

How could such a basic algorithm triumph over programs designed with complex predictive models and Machiavellian logic? Axelrod's analysis of the results revealed the key ingredients for successful cooperation, which Tit for Tat embodied perfectly. He identified four properties that high-scoring strategies shared:

- It was Nice: A "nice" program is one that is never the first to defect. By starting with cooperation, Tit for Tat immediately signaled a willingness to work together, opening the door for mutually beneficial outcomes and avoiding unnecessary conflict.

- It was Retaliatory (or Provocable): Tit for Tat was no pushover. If an opponent defected, it would immediately retaliate on the next move. This swift punishment made it clear that exploitation would not be tolerated, deterring aggressive strategies from trying to take advantage of it.

- It was Forgiving: This is arguably its most important trait. After retaliating for a defection, if the opponent returned to cooperation, Tit for Tat would immediately "forgive" and cooperate on the next turn. It didn't hold a grudge. This ability to break cycles of mutual recrimination was vital for re-establishing trust and returning to the high-scoring rhythm of cooperation.

- It was Clear: Its strategy was simple and transparent. Opponents quickly learned its rules. They could understand that cooperation would be rewarded and defection would be punished. This clarity and predictability made it a reliable partner in cooperation.

The Cast of Characters: A Look at the Key Players

To make the tournament more concrete, let's meet some of the digital "personalities" that competed. While dozens of strategies were submitted, they can often be grouped into different archetypes. Here is a look at some of the most notable contenders and their performance.

(Note: The "Rank" is a generalization. In reality, performance depended on the specific mix of other strategies in the tournament, but this reflects the general outcomes.)

| Strategy Name | Brief Description | Key Trait(s) |

| 1st place | ||

| Tit for Tat | Cooperates on the first move, then copies the opponent's previous move. | Nice, Retaliatory, Forgiving, Clear |

| Top-Tier | ||

| Tester | Defects on the first move to "test the waters." If the opponent retaliates, it apologizes and plays Tit for Tat. If not, it keeps defecting. | Probing, but ultimately cooperative with non-suckers. |

| Friedman (Grim Trigger) |

Cooperates until the opponent defects even once, after which it defects forever. | Nice, Grimly Retaliatory, Unforgiving |

| Tit for Two Tats | A more forgiving version. Only defects after the opponent has defected twice in a row. | Very Nice, Forgiving, Resists echo effects |

| Mid-Tier | ||

| Joss | A "sneaky" version of Tit for Tat. Mostly mimics the opponent but has a 10% chance of defecting instead of cooperating. | Mostly Nice, Retaliatory, but "Treacherous" |

| Downing | Starts by trying to model its opponent. If the opponent seems responsive and has a "conscience," it cooperates. If the opponent seems random or unresponsive, it defects to protect itself. | Adaptive, Calculating, not inherently "Nice" |

| Lower-Tier | ||

| Always Defect (ALL D) | Always chooses to defect, no matter what. | Nasty, Aggressive |

| Random | Cooperates or defects with a 50/50 chance. | Unpredictable, Unreliable |

| Bottom-Tier | ||

| Always Cooperate (ALL C) |

Always chooses to cooperate, no matter how many times it's betrayed. | Nice, but Naive and Exploitable |

| Nydegger | A more complicated rule-based strategy that tried to be a more forgiving Tit for Tat, but its logic was flawed and exploitable, leading to poor performance. | Well-intentioned, but Confused and Exploitable |

This table clearly shows that the most successful strategies were "nice" (they were never the first to defect), but they were not pushovers. The purely aggressive (ALL D) and purely naive (ALL C) strategies performed very poorly, as they were exploited or locked into mutually destructive patterns.

The Second Round and the Lasting Legacy

Thinking the results might have been a fluke, Axelrod held a second, even larger tournament. This time, participants knew the results of the first round. They knew about Tit for Tat's success and could design strategies specifically to beat it. Sixty-two entries came in from all over the world.

And Tit for Tat won again.

Its robustness was proven. The simple principles of being initially kind, swift but proportional in retaliation, immediately forgiving, and clear were not just a winning formula; they appeared to be a fundamental recipe for the evolution of cooperation.

Theory vs. Noisy Reality

Before we hail Tit for Tat as the miracle cure for all of life's conflicts, it's crucial to remember that Axelrod's tournament took place in a clean, digital "laboratory." The programs executed their instructions flawlessly, there were no misunderstandings, and every move was clearly either cooperation or defection.

While the principles discovered are invaluable, real life is rarely so sterile. It is filled with miscommunication, accidents, and misinterpreted intentions. Game theory describes this unpredictability as "noise," and its presence can fundamentally change a strategy's effectiveness.

In a noisy environment, even Tit for Tat becomes vulnerable. Imagine two Tit for Tat players happily cooperating. A single misunderstanding causes one player's cooperative move to be perceived as a defection. Following its rules, the second player immediately retaliates. The first player, unaware of the initial mistake, sees this as an unprovoked defection and retaliates in turn. The two can become locked in a "death spiral" of mutual retaliation, a digital blood feud, all because of one random error.

This is precisely why later work and tournaments explored more robust variations, such as Tit for Two Tats (which only defects after two consecutive defections), Generous Tit for Tat (which occasionally forgives a defection), and Win-Stay, Lose-Shift (Pavlov), all of which can outperform standard Tit for Tat under various error rates and population dynamics. Acknowledging this nuance helps explain why the dynamics of cooperation sometimes differ between the lab and the real world.

Formally, the sustainability of cooperation in repeated prisoner's dilemmas hinges on two components: the ordering of payoffs and the value of future interaction. Payoffs must adhere to the T > R > P > S (Temptation > Reward > Punishment > Sucker) condition, and players must value future payoffs sufficiently (a high probability of continuation or a low discount rate). When these conditions hold and interactions are repeated with reasonable certainty, reciprocal strategies can become self-enforcing—a bridge between Axelrod's empirical tournaments and the theoretical findings of repeated game theory.

Beyond the Simulation: The Logic of Cooperation in the Wild

The question naturally arises: are the lessons from Axelrod's digital arena mere theoretical curiosities, or do they reveal real patterns in the human and natural world? Do the core principles of Tit for Tat—niceness, retaliation, and forgiveness—truly form the universal building blocks of cooperation?

The answer is fascinating. It turns out this logic appears again and again in the most unexpected places, proving that cooperation has deep evolutionary and social roots. Below are a few cases where the principles of Tit for Tat emerged spontaneously, without any top-down design.

The Most Striking Example: The Trenches of World War I

Perhaps the most poignant real-world parallel to Axelrod's findings comes from a place where we would least expect cooperation: the trenches of World War I. During long periods of stalemate on the Western Front, a spontaneous, informal system of truce emerged between opposing British and German troops. This phenomenon became known as the "Live and Let Live" system.

It worked exactly like an organic game of Tit for Tat:

- Be Nice (Don't Shoot First): A unit would signal its peaceful intentions with predictable, non-lethal routines. For example, they might shell the same empty part of the trench at the same time each day. This was a "cooperative" move.

- Retaliate: If one side suddenly launched a deadly, unprovoked raid (a "defection"), the other side would immediately retaliate with a fierce counter-attack to show that aggression would not be tolerated.

- Be Forgiving: Crucially, after the retaliation, the attacked side would often revert to its previous "cooperative" routine, signaling a willingness to restore the truce. They did not hold a grudge forever.

This unspoken system of cooperation emerged without orders from high command (in fact, generals actively tried to stamp it out). It arose from the self-interest of soldiers on both sides, who recognized they were in a repeated game. They knew they would be facing the same opponents tomorrow, and the day after. The "shadow of the future" loomed large, and they realized that mutual restraint was far better for their survival than constant, unbridled aggression.

This powerful historical example shows that the principles discovered in Axelrod's computer tournament are not just abstract theory. They are a fundamental part of human survival and cooperative strategy, even in the most hostile environments imaginable. The logic of Tit for Tat is not limited to human conflict. It can be observed in other domains:

- Vampire Bat Reciprocity: In biology, a classic example of reciprocal altruism is the behavior of vampire bats. These animals feed on blood, but a night's hunt can be unsuccessful. A bat that returns to the roost hungry is often fed regurgitated blood by a well-fed roost-mate. Studies have shown that bats are more likely to share food with a bat that has previously helped them. This is a clear Tit for Tat strategy: cooperate (share blood) with those who have cooperated with you, and don't help those who have refused to help in the past (retaliation).

- Business Relationships and Pricing: In economics, the (often tacit) pricing agreements between firms can follow this pattern. Two competitors can avoid a mutually destructive price war (mutual cooperation). But if one company suddenly slashes prices to gain market share (defection), the other will almost immediately follow suit (retaliation), ultimately hurting both firms' profits. Stability is only restored when they return to the previously understood price level (forgiveness).

These examples highlight how Axelrod's experiment uncovered a fundamental mechanism that allows trust and cooperation to emerge even among self-interested, rational actors, provided their relationship is long-term.

Conclusion

Axelrod's work, culminating in his 1984 seminal book The Evolution of Cooperation, has had a profound impact far beyond game theory. Biologists have used it to model reciprocal altruism in animal populations. Economists have applied it to understand trust in business relationships. Political scientists have seen its reflection in international diplomacy and arms control treaties during the Cold War.

Today, these simple principles of reciprocity inspire work beyond the social sciences: designers of multi-agent systems, decentralized protocols and blockchain incentive mechanisms, and teams of interacting AIs all face the same trade-offs between exploitation and cooperation. The design of robust reciprocity rules—those that tolerate noise and scale across populations—remains central to engineering cooperative behavior in both human and artificial systems.

The tournament taught us a powerful lesson: cooperation requires neither a central authority nor selfless altruism. It can emerge spontaneously among self-interested individuals, so long as they know they will meet again. In a world that often seems complex and cynical, the triumph of Tit for Tat is a hopeful and enduring reminder that the best strategy is often to be nice, but not naive; forgiving, but not forgetful; and above all, clear and consistent in our actions.

Historically, these tournaments were organized and analyzed by Robert Axelrod, who coordinated submissions and synthesized the findings in his influential work. The strategy known as Tit for Tat—often credited to Anatol Rapoport as an early proponent—was made famous by Axelrod's analysis. For the canonical presentation of the experiment and its implications, see Axelrod's work (Axelrod & Hamilton, 1981; Axelrod, 1984). Later theoretical and empirical studies (e.g., Nowak & Sigmund, 1993) have deepened our understanding, showing when and why other reciprocity rules (like Win-Stay, Lose-Shift or more generous variants) can outperform simple Tit for Tat under different conditions.