The Selfless Enforcer: Why Do We Pay to Punish Others?

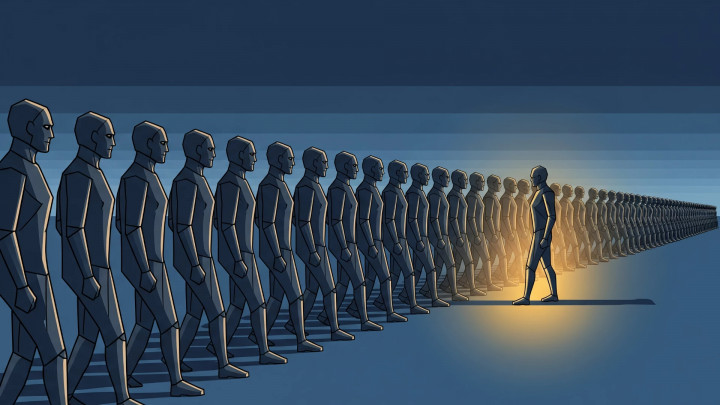

You know the feeling. Someone shamelessly cuts in front of you in line, talks loudly on their phone in the quiet train car, or simply doesn't pull their weight on a team project. Although their actions might not harm you directly, your blood boils. You feel a powerful urge to confront them, even if it means putting yourself in an awkward situation. This deep-seated indignation, born from a sense of justice, is more than just a fleeting annoyance. It's one of the most powerful, mysterious, and controversial engines of human cooperation: altruistic punishment.

The mechanisms we've discussed so far—the various forms of reciprocity and network structures—have shown how cooperation can emerge and persist in the hope of future returns or within the safety of a community. But what happens in larger, more anonymous groups, where reputation matters less and the chances of future encounters are slim? In these situations, the free-rider problem thrives: the temptation to enjoy the benefits of a public good without contributing to it.

How do societies combat this incredibly corrosive force? The groundbreaking experiments of Swiss economists Ernst Fehr and Simon Gächter provided a stunning answer: we are willing to make personal sacrifices to punish the selfish, even when we gain no direct material benefit from doing so.

The Social Experiment That Exposed Selfishness: The Public Goods Game

The genius of Fehr and Gächter lay in their ability to model the free-rider dilemma in a laboratory setting using a simple exercise called the Public Goods Game. The setup is as follows:

- A group of four strangers each receives 20 monetary units.

- In each round, every player secretly decides how much of their 20 units to contribute to a "common pot."

- At the end of the round, the experimenter multiplies the total amount in the pot (e.g., by 1.6) and then divides the sum equally among all four players, regardless of how much they individually contributed.

The logic is clear: the best outcome for the group is if everyone contributes all 20 units, as this maximizes the collective payoff. For the individual, however, the most tempting strategy is to free-ride: contribute nothing, but still collect a share of the multiplied contributions of others. The first phase of the experiments yielded a depressing but predictable result: after just a few rounds, trust evaporated, and contributions plummeted to nearly zero. Cooperation collapsed.

The Twist: The Power to Punish

Then came the second, game-changing phase of the experiment. The players were given a new option: at the end of each round, after seeing everyone's contributions, they could spend their own money to punish others. For every monetary unit a player spent on punishment, three units were deducted from the punished player's earnings.

From a classical economic standpoint, this decision seems purely irrational. Why would you pay to harm a stranger you will never meet again, especially when their punishment provides you with no financial gain?

The result was dramatic. Players used the punishment option extensively. They began to heavily penalize those who contributed less than the group average, especially the absolute free-riders. The effect was immediate: fearing punishment, the level of cooperation soared and remained high for the rest of the experiment. The participants had voluntarily maintained a costly enforcement system, saving the public good from total collapse.

Why Is the Punishment "Altruistic"?

The phenomenon is called altruistic punishment because the act of punishing is selfless from the group's perspective. The punisher incurs a personal cost (losing the money spent on the punishment) to penalize a norm-violator. From this single act, they receive no direct, personal benefit. The benefit accrues to the group as a whole: the deterrent effect of punishment stabilizes the cooperative norm, and in future rounds, everyone (including the punisher) profits from the higher level of cooperation. The punisher, therefore, makes an individual sacrifice for the common good.

The Evolution of Justice and Its Double-Edged Sword

But what drives this behavior? Research suggests the key lies in our deeply wired emotions. When we witness injustice or the violation of a social norm, our brain's reward centers activate if we are given the opportunity to punish the cheater. Administering punishment feels good; it satisfies our sense of justice. It’s likely that early human groups containing such "selfless enforcers" were far more effective at maintaining internal order and cooperation, giving them an evolutionary advantage over groups composed of purely selfish individuals.

This mechanism is a cornerstone of modern societies. When we pay taxes, we collectively fund the police and the justice system—this is an institutionalized form of the same phenomenon. But it also operates constantly in our daily lives: social disapproval, gossip, public shaming, and even certain aspects of modern phenomena like "cancel culture" can be interpreted as manifestations of altruistic punishment.

However, it is crucial to recognize that this mechanism is a double-edged sword. The same force that upholds a just and cooperative norm can be used to enforce an arbitrary, exclusive, or oppressive one. Peer pressure, the demand for conformity, and the punishment of "dissidents" are all fed by this same instinct. The mechanism itself is neutral; whether its power is constructive or destructive depends entirely on the moral quality of the norm it serves.

Conclusion: The Strong Guardian of Cooperation

The discovery of altruistic punishment revealed that human cooperation is not based solely on calculated self-interest or passive structural advantages. We possess a proactive, emotionally charged instinct that drives us to stand guard over our community's norms and to punish those who violate them, even at a personal cost. This tendency, though it may sometimes seem irrational and expensive, is in fact one of the most critical factors that allows us to trust and cooperate in large groups of strangers. It is the strong, but sometimes blind, guardian of cooperation, without which our societies would be far more fragile.