Why We Say Yes When We Think No

Picture this: you’re in a room with eight other people, participating in a simple perception test. The task is straightforward: you must identify which of the three lines on the right is the same length as the reference line on the left. You look at it, and the answer is as obvious as the sky is blue. You’re confident.

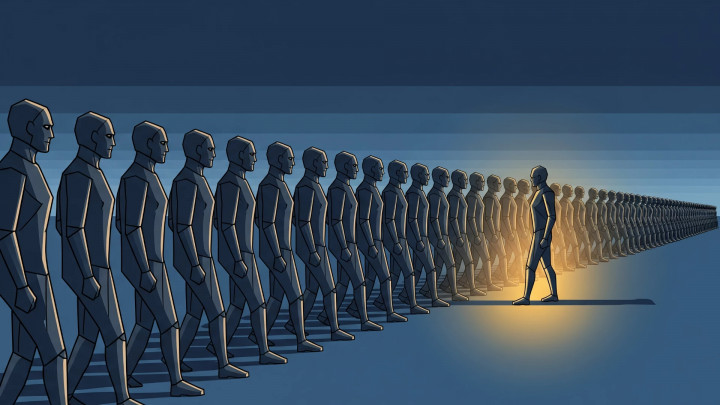

Then, the others begin to answer, one by one, out loud. The first person gives a clearly wrong answer. Strange, you think, maybe their vision is off. Then the second person gives the same incorrect answer. And the third, and the fourth, and all the others. By the time it’s your turn, everyone in the room has unanimously stated something that is obviously false to your own eyes. What do you do? Do you stick with what you see, or do you conform to the group?

This very dilemma was at the heart of a fascinating series of experiments conducted in the 1950s by Solomon Asch, a pioneer of social psychology. The question he posed is timeless: can group pressure override our own clear perception? The answer is far more unsettling than we might think.

An Innocent-Looking Vision Test

Asch's experiment was brilliant in its simplicity. He told participants (who were university students) they were taking part in a vision test. He showed them the lines, as described above, and they had to state their answer aloud.

The twist, however, was that in each group, there was only one true, "naive" subject. The rest were all confederates—actors working for Asch who followed a predetermined script. The unsuspecting participant was deliberately seated to be one of the last to answer, forcing them to listen to the unanimous (and intentionally wrong) opinions of the others first.

The experiment consisted of 18 rounds, or "trials," each with a different set of lines. In the first few trials, everyone gave the correct answer to build trust and make the situation seem credible. But then, in 12 of the 18 "critical trials," all the confederates gave the same, blatantly wrong answer.

Moments of Internal Conflict

You can almost picture the confusion on the subject's face. After the first incorrect answer, they might have smiled, thinking someone was joking. By the second, a furrowed brow would appear. After the third and fourth, their initial confidence would evaporate, replaced by anxiety and doubt. "Is something wrong with me? Am I seeing the angle incorrectly? Is there something here I’m not getting?"

Participants would start to fidget, mumble to themselves, or laugh nervously. The dilemma became palpable in the room: should I trust my own senses and risk looking like a fool, or should I trust the group and deny what I see with my own eyes?

The Shocking Results in Numbers

Asch's findings remain a cornerstone of social psychology to this day because they illuminated a profound human tendency.

- 75% of participants conformed to the group pressure at least once, giving the obviously wrong answer.

- Across all critical trials, 37% of all responses were conforming, meaning they matched the group's incorrect answer.

- For comparison, in a control group where participants gave their answers in private without group pressure, the error rate was less than 1%.

This stark difference proved that it wasn't the difficulty of the task but solely the pressure from the group that caused the dramatic increase in errors.

Why? The Psychology of Conformity

But why did people do this? In post-experiment interviews, Asch identified two primary reasons:

- Normative Conformity (The Desire to Fit In): Most participants who gave the wrong answer knew the group was incorrect. They conformed anyway because they feared rejection, ridicule, or being seen as a "troublemaker." They didn't want to rock the boat. This painfully human desire to belong proved stronger than their commitment to stating the truth.

- Informative Conformity (The Search for the Right Answer): A smaller group of participants genuinely began to doubt their own judgment. They thought, "If all these people see the same thing, I must be the one who's wrong." In this case, the individual looks to the group as a more reliable source of information than their own senses, especially in an ambiguous situation (which the group's unanimity created).

But let's take a step back. Why is this urge to fit in and accept the group's opinion so powerful? The answer lies deep in our evolutionary past. For millennia, human survival depended on the group.

- The Pack Mentality as a Survival Strategy: A lone early human was easy prey for predators and helpless against the elements. The group meant protection, security, and more effective resource gathering. An individual cast out from the group was, in essence, handed a death sentence. This brutal selective pressure has hardwired an elemental need for belonging into our DNA. Our brains evolved to perceive social rejection as a genuine, physical threat. When a participant in the experiment went against the group, their brain's alarm centers may have activated just as they would in the face of real danger.

- The Wisdom of the Crowd (or the Assumption of It): In our ancestral environment, group consensus often carried life-saving information. If every member of the tribe suddenly started running in one direction, the smart move wasn't to stop and look for the lion—it was to run with them. Those who hesitated didn't pass on their genes. This is the ancient mechanism of "informative conformity": the group's opinion serves as a fast, efficient, and usually reliable shortcut (a heuristic) for understanding the world.

So, the behavior seen in Asch's experiment isn't just a sign of momentary weakness. It’s an evolutionary echo—a deep, ancient survival instinct reverberating within the sterile walls of a modern psychology lab.

A Glimmer of Hope: One Ally Is All It Takes

Asch didn't stop there. He ran numerous variations of the experiment, which yielded perhaps even more important lessons. The most powerful result came when he introduced an "ally" into the group of confederates—one other person who consistently gave the correct answer.

The result? Conformity plummeted by nearly 75%! All it took was one other person to validate the participant's own perception, and they found the courage to stand by their truth. This shows that social support is an incredibly potent antidote to group pressure.

The Legacy of the Asch Experiment: Why It Matters Today

A 1950s experiment about judging lines may seem distant, but its lessons are more relevant than ever. Just think about:

- Workplace meetings: How often do we nod along to a bad idea simply because the boss and the majority support it?

- Peer groups: Do we dare to speak up when our friends are unfairly criticizing someone?

- Social media: How many people follow a trend or share an opinion without critical thought, just because "everyone is doing it"?

- History: The experiment helps us understand how social phenomena could arise where entire populations followed clearly flawed or immoral ideologies.

Echoes of the Experiment: Supporters and Critics

Like any landmark scientific study, Asch's conformity experiment has been debated and analyzed by supporters and critics, all of whom have shaped our understanding of its findings.

Supporters

The overwhelming majority of social psychologists still regard Asch's work as fundamental. Their main argument is that the experiment elegantly and irrefutably demonstrated the power of social pressure in a controlled, laboratory setting. It showed that group influence is not just an abstract concept but a measurable and potent force capable of overriding even basic sensory perception. Asch's findings paved the way for other hugely influential studies, such as Stanley Milgram's obedience experiments (Milgram was a student of Asch), which examined submission to authority.

Critical Voices

Over the decades, however, several critiques have emerged that add nuance to the interpretation of the results.

- Artificial Setting (Low Ecological Validity): The most common criticism is that the lab setting was too artificial. In real life, we rarely find ourselves judging the length of lines with a group of strangers. The stakes were incredibly low—there were no real consequences for being wrong. Critics argue that people might not abandon their convictions so easily when it comes to an important moral or personal issue.

- Cultural and Historical Context: The experiments were conducted in 1950s America, an era characterized by Cold War paranoia and a strong culture of social conformity (the McCarthy era). Replications of the study in other cultures (especially in more individualistic Western societies) have often shown lower rates of conformity. Conversely, studies in more collectivist cultures (e.g., in Asia) have typically found higher rates. This suggests that the degree to which people yield to group pressure is heavily influenced by culture.

- An Overemphasis on Conformity: Some critics argue that Asch and his followers focused too much on the conformity and not enough on the resistance. Let's not forget that nearly two-thirds (63%) of the total responses in the critical trials correctly defied the group! One could interpret the results as a testament to the remarkable power of human independence and integrity. Asch himself was reportedly surprised by how many people were able to resist.

These critiques don't invalidate the fundamental importance of the experiment, but they remind us that human behavior is incredibly complex and that we must always consider situational, cultural, and individual factors.

Conclusion

Solomon Asch's experiment doesn't prove that people are weak-willed. Rather, it reveals that we are profoundly social creatures whose perception of reality is heavily influenced by those around us. But it also reminds us of the importance of courage—the courage it takes to say, "I might be alone in this, but Line B is the correct answer."

And let's not forget the 25%—the participants who never, not even once, gave in to the pressure. They are the proof that autonomy and integrity are possible, even in the face of overwhelming pressure.