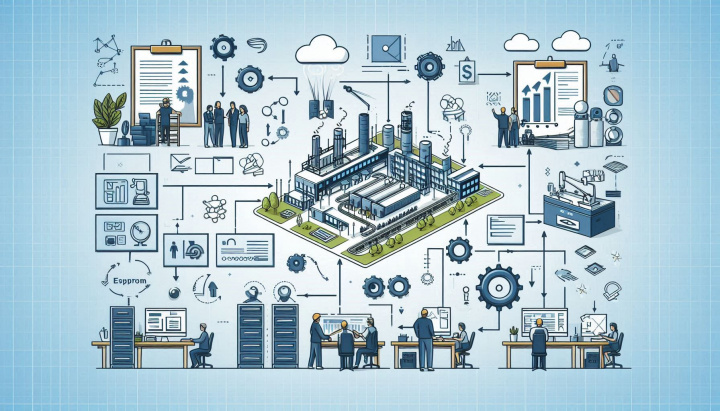

LEAN Method: Minimize Waste, Maximize Efficiency, and Drive Continuous Improvement

The LEAN method is a powerful management philosophy and process improvement system focused on maximizing customer value by minimizing waste and enhancing process efficiency. Originating with the Japanese automotive giant Toyota in the 1950s as the Toyota Production System (TPS), LEAN principles have proven highly adaptable and are now successfully applied across countless sectors worldwide, including manufacturing, healthcare, software development, services, and government.

The Origins of the LEAN Method

The roots of the LEAN method trace back to the post-World War II era in Japan. Facing severe resource constraints, Toyota, under the guidance of engineers like Taiichi Ohno and Shigeo Shingo, developed the Toyota Production System (TPS). Their goal was ambitious: to shorten the time between customer order and vehicle delivery by relentlessly eliminating non-value-adding activities. TPS focused on creating flow, reducing inventory (Just-in-Time), highlighting problems immediately (Jidoka), and empowering workers. This innovative system laid the foundation for what the world now recognizes as LEAN thinking, a term popularized by James Womack, Daniel Jones, and Daniel Roos in their book "The Machine That Changed the World."

The Essence of the LEAN Method: Core Principles and Waste Elimination

At its heart, LEAN thinking revolves around delivering value from the customer's perspective while consuming the fewest possible resources. This is achieved by systematically identifying and eliminating waste, known in Japanese as "muda". Waste encompasses any activity that consumes resources but creates no value for the customer. There are commonly recognized eight types of waste (Muda):

- Defects: Producing faulty products or services requiring rework or scrapping.

- Overproduction: Producing more, earlier, or faster than required by the next process or customer.

- Waiting: Idle time caused by delays, bottlenecks, or unsynchronized processes.

- Non-Utilized Talent: Failing to leverage the skills, knowledge, and creativity of employees.

- Transportation: Unnecessary movement of materials or information between processes.

- Inventory: Holding excess raw materials, work-in-progress, or finished goods.

- Motion: Unnecessary movement of people (e.g., walking, searching, reaching).

- Extra-Processing (Over-processing): Performing work that is not valued by the customer or using overly complex processes.

The LEAN approach is guided by five core principles:

-

Define Value: Clearly articulate what constitutes value from the customer's perspective for a specific product or service.

-

Map the Value Stream: Identify all the steps (both value-adding and non-value-adding) currently required to deliver that value, from raw material to the customer. This helps visualize waste.

-

Create Flow: Reconfigure the value-adding steps to occur in a tight, uninterrupted sequence, eliminating delays, bottlenecks, and queues wherever possible.

-

Establish Pull: Institute a system where downstream processes signal their needs to upstream processes. Nothing is produced or moved until there is a real demand, minimizing overproduction and inventory.

-

Pursue Perfection (Kaizen): Foster a culture of Kaizen (continuous improvement) where everyone in the organization is engaged in systematically identifying and eliminating waste and refining processes incrementally and perpetually.

LEAN Case Studies and Examples

The power of LEAN is evident in its successful application across diverse industries:

-

Toyota Automotive Manufacturing: The birthplace of LEAN, Toyota exemplifies its principles through its renowned production system. Features like Just-In-Time inventory, Kanban signaling, and continuous flow lines allow Toyota to produce high-quality vehicles efficiently, adapt quickly to market shifts, and maintain global competitiveness.

-

Zara (Inditex) Fashion Retailer: Zara revolutionized the fashion industry by applying LEAN principles to its supply chain. By using a highly responsive design-to-retail process, small batch production, frequent store deliveries, and minimized inventory, Zara can rapidly bring the latest trends to market, reducing markdowns and waste.

-

NHS (National Health Service) UK: In healthcare, LEAN has been used to streamline patient pathways, reduce waiting times for appointments and procedures, optimize lab processes, improve inventory management of medical supplies, and enhance overall patient safety and experience, often leading to better outcomes with existing resources.

-

Amazon Fulfillment Centers: Amazon's logistics network heavily relies on LEAN principles to manage its vast scale. Standardized work, optimized layouts to minimize motion and transportation, sophisticated inventory management, continuous flow of packages, and data-driven process improvements are key to their speed and efficiency in fulfilling customer orders.

Practical Application of LEAN: Tools and Culture

Successfully implementing LEAN involves more than just understanding the principles; it requires practical application using specific tools and fostering a supportive organizational culture. Key steps include:

- Process Analysis: Thoroughly analyzing existing processes using tools like Value Stream Mapping (VSM) to visualize flow and identify waste.

- Workplace Organization: Implementing methods like 5S (Sort, Set in Order, Shine, Standardize, Sustain) to create clean, organized, and efficient workspaces where problems are easily visible.

- Flow and Pull Management: Using tools like Kanban systems (visual signals for replenishment or production) to manage workflow and implement pull.

- Error Proofing: Applying Poka-Yoke techniques to design processes that prevent mistakes from happening.

- Employee Engagement: Crucially, LEAN requires active participation from everyone. Empowering employees to identify problems and suggest improvements (Kaizen) is fundamental.

- Leadership Commitment: Sustained success depends on strong leadership commitment to LEAN principles, providing resources, removing obstacles, and leading by example.

Adopting LEAN is a journey, not a one-time project. It demands continuous monitoring of performance metrics (e.g., lead time, cycle time, defect rates, inventory turns), data-driven decision-making, and a relentless focus on eliminating waste and improving value delivery.

In conclusion, the LEAN method offers a robust framework for organizations seeking to enhance their performance significantly. By focusing on customer value, eliminating the eight wastes, and cultivating a culture of continuous improvement, companies can achieve substantial benefits. These often include reduced lead times, lower operating costs, improved quality, increased productivity, higher employee morale, and greater agility in responding to market changes. Embracing LEAN principles is a strategic investment that drives long-term competitiveness and sustainable growth.