The Prosperity Paradox: Do Good Times Create Weak People?

A popular anecdote suggests that prosperity can one day turn on itself: hard times create strong people, strong people create good times, good times create weak people, and weak people create hard times. This idea is often cited in discussions about the rise and fall of great civilizations. Yet, it begs the question: how universal is this "law," and where does the line between historical insight and rhetorical exaggeration lie?

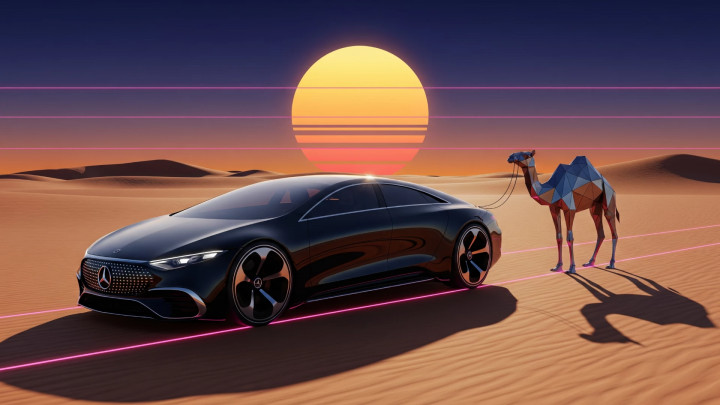

“My grandfather rode a camel, my father rode a camel, I drive a Mercedes, my son drives a Land Rover, his son will drive a Land Rover, but his son will have to ride a camel...”

“Why is that?”

“Hard times create strong men. Strong men create easy times. Easy times create weak men. Weak men create hard times. Many will not understand it, but we have to raise people who can create and fight—not just consume.”

This quote, often attributed to Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, the modern architect of Dubai (though its exact source and literal wording are difficult to verify, the sentiment perfectly aligns with his life experience and vision), captures one of human history's most unsettling paradoxes with pinpoint accuracy. The saying comes from a leader who personally witnessed a desert pearl-diving port transform into one of the world's wealthiest metropolises. But is this just a dramatic warning, or is it an iron law governing the rise and fall of civilizations? In this article, we will explore this idea through the lenses of history, sociology, and philosophy.

The Anatomy of the Cycle

Before we delve deeper, it's worth breaking down the logic of the model. The concept outlines a four-phase, self-perpetuating cycle:

- Hard Times → Strong People: Scarcity, the constant struggle for survival, and external threats forge generations that are resilient, resourceful, disciplined, and highly motivated. They have no other choice: their success means their survival. They are the "warriors" who can create value and stability from nothing.

- Strong People → Good Times: This hardened generation, through hard work, sacrifice, and wise decisions, builds a prosperous society. They establish the peace, security, and economic well-being in which future generations can grow up.

- Good Times → Weak People: The generation born into established prosperity tends to take it for granted. Having never had to fight for it, they don't understand its true value. Comfort makes them complacent, and a constant sense of security diminishes their risk appetite and problem-solving skills. They are more likely to consume the wealth of their predecessors than to build upon it. They are the ones who see prosperity as a given, something to be enjoyed rather than recreated.

- Weak People → Hard Times: When new, serious challenges arise (an economic crisis, a war, a natural disaster), this unprepared, complacent generation is incapable of responding effectively. They make poor decisions and lack the perseverance and self-sacrifice needed, ultimately leading to the decline and collapse of the system they inherited. The circle closes, and hard times return.

Echoes of History: Where Have We Seen This Pattern?

This model isn't just a theoretical exercise. History is filled with examples that bear an uncanny resemblance to this cycle.

- The Fall of the Roman Empire: The classic case. The early Roman Republic was built by hardy, farmer-soldier citizens ("strong people"). Through their conquests, they created unimaginable wealth and peace (Pax Romana—"good times"). Centuries later, the Roman elite lived in decadence and luxury, while the urban masses were kept content with free grain and spectacular games (panem et circenses). Society lost its inner strength, and the empire, led by "weak people," was unable to withstand internal crises and external barbarian invasions. Of course, the reasons for its decline were more complex—economic, military, and administrative factors all played a role—but the pattern is nevertheless recognizable.

- Ibn Khaldun and the Law of the Desert: Perhaps no one articulated this cycle more scientifically than the 14th-century Arab polymath, Ibn Khaldun. He introduced the concept of asabiyyah, which signifies group cohesion, social solidarity, and a shared sense of purpose. He argued that nomadic desert tribes (living in "hard times") possess an extremely strong asabiyyah. This enables them to conquer a softened, urban civilization. However, once they adopt a comfortable lifestyle, their asabiyyah erodes within a few generations, and they are, in turn, subjugated by a new, strong group.

A Tradition of Cyclical Thought

Behind the wisdom of the quote lies a long philosophical tradition that examines the repetition of history and the life cycles of civilizations. Many great thinkers have concluded that history does not move in a straight line.

- Oswald Spengler, in his early 20th-century work The Decline of the West, compared cultures to living organisms that are born, mature, grow old, and die. He argued that Western civilization had entered its final, declining phase, characterized by materialism and spiritual emptiness.

- British historian Arnold J. Toynbee explained the fate of civilizations with his "challenge and response" theory. The key to rising is successfully responding to challenges, while a fall occurs when a civilization's creative elite loses its vigor and can no longer cope with new problems.

- Peter Turchin, the father of modern "cliodynamics," uses mathematical models to study history. His theory suggests that long periods of peace ("good times") lead to elite overproduction and growing social inequality, which eventually result in internal conflict and political instability ("hard times").

Does History Really Come Full Circle?

In recent decades, social sciences have attempted to capture the cyclical changes of civilizations with data. Peter Turchin and his colleagues, for instance, have analyzed centuries of data on population, elite overproduction, and internal conflict in their "cliodynamic" models. Their findings suggest that during periods of peace and prosperity, the number of elites grows faster than economic opportunities, leading to increased social tensions and, eventually, crises.

However, other indicators paint a more nuanced picture. Research by Steven Pinker shows that long-term trends—such as rates of violence, war-related deaths, child mortality, and extreme poverty—have drastically declined over the past two centuries. The tension between these two perspectives highlights that history doesn't follow a single pattern. While some societies may indeed falter in an era of plenty, humanity as a whole still learns and progresses. This might suggest that the "cycle" is not a perfect circle—perhaps it's more of a spiral.

Can the Cycle Be Broken? The Counterarguments

Naturally, the cyclical view of history has its critics, especially among those who believe humanity is capable of collective learning and progress. Many argue that history is not a deterministic cycle.

- The Enlightenment and Linear Progress: Thinkers of the 18th century, like Condorcet, believed that through human reason and science, humanity is constantly advancing toward a better and more developed state. According to this view, history is an upward trajectory, not a vicious circle.

- The Skepticism of Modern Historiography: Most contemporary historians are wary of grand, all-encompassing theories. They argue that such models oversimplify a complex reality, ignore the role of chance, and underestimate the power of human agency in shaping our destiny.

- Steven Pinker and Fact-Based Optimism: The Harvard psychologist uses data to argue that, despite pessimistic predictions, the world is becoming a better place by many metrics (violence, poverty, disease). This perspective suggests we are capable of learning from past mistakes and consciously avoiding decline.

The Question Remains Open

Returning to Sheikh Rashid's quote, we must recognize that its power lies not in its scientific precision but in its metaphorical depth. The fate of civilizations may not be an unstoppable cycle operating with iron logic. But the warning—that comfort can soften us, and prosperity can make us forget the very virtues (perseverance, humility, sacrifice) that made that prosperity possible—remains as valid today as ever.

Perhaps the biggest question we can ask ourselves in the relative peace and abundance of the 21st century is this: we are the children of history's most comfortable era, the offspring of "good times." Will we be able to break the pattern? Can we use our prosperity to become not weaker, but wiser and more prepared?

Or does the wheel of history truly turn inexorably—and will our grandchildren have to learn how to ride camels once again? Perhaps, for the first time, humanity will manage to break the cycle, transforming prosperity not into weakness, but into enduring wisdom.