Islands of Kindness: How Cooperation Survives in a Sea of Selfishness

Have you ever wondered why, despite the selfishness and conflict that seem to dominate the news and social media, you still experience functional cooperation in your immediate surroundings—among family, friends, and colleagues? This paradox leads us to one of the most fascinating puzzles in the evolution of cooperation.

Classic models often imagine society as a large, "well-mixed" pool where anyone can interact with anyone else. Under these conditions, a selfish, cheating strategy can spread like wildfire. But what if reality isn’t like that? What if the very structure of society, the intricate web of our relationships, offers its own protection for cooperation?

The work of Robert Axelrod, and later Martin Nowak and Karl Sigmund, revolutionized our thinking about cooperation by demonstrating the power of direct and indirect reciprocity. However, even these models often relied on the simplification that the population was "well-mixed," meaning everyone had an equal chance of encountering everyone else. In reality, our lives are not like that. We live in structured networks: we have neighbors, colleagues, and friends, and the vast majority of our interactions happen with them.

This crucial insight was the focus of a groundbreaking 1992 paper in Nature by Martin Nowak and the renowned theoretical biologist Robert May. Their work established the theory of network or spatial reciprocity, showing that for cooperation to survive, it doesn’t need to conquer the entire world at once. It just needs to find a small, protected corner to gain a foothold.

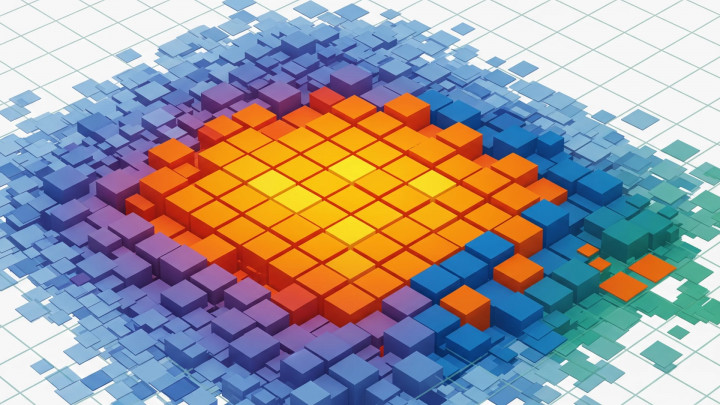

The Revolutionary Insight: Cooperation on a Chessboard

Nowak and May’s model was brilliantly simple. Instead of studying a chaotic, well-mixed population, they created a simple grid, much like a chessboard. Each square represented a player who could adopt one of two strategies: cooperator or defector. The twist was in the rules:

- Local Interactions: Players didn't play with everyone. They interacted exclusively with their immediate neighbors (the eight squares surrounding them).

- Local Success: At the end of each round, players’ scores were tallied based on these local interactions.

- Adaptation: For the next round, each player adopted the strategy of the most successful individual in their local neighborhood (including themselves). If a neighboring defector had the highest score, they became a defector. If a cooperator was winning, they adopted cooperation.

The results of their simulations were stunning. In well-mixed models, when the reward for defection was high enough, defectors inevitably wiped out cooperators. On the spatial grid, however, a completely different dynamic emerged. Cooperators were able to form clusters, creating stable "islands" of mutual support.

While cooperators on the edges of these clusters were vulnerable to neighboring defectors, those inside the cluster found themselves in a protected haven. They interacted exclusively with other cooperators, consistently earning high scores and reinforcing each other. Defectors simply couldn't penetrate the heart of these cooperative blocks. The result was a dynamic, ever-shifting landscape where islands of kindness survived and thrived in a sea of selfishness.

The lesson was clear: social structure itself can be an engine of cooperation. Cooperation doesn't have to win globally; it just has to succeed locally.

From Grids to Social Networks: The Principle in the Digital Age

Nowak and May's 1992 model is more relevant today than ever. In the 21st century, the concept of a "spatial neighbor" is no longer primarily about physical proximity. Our neighbors are our Facebook friends, our Twitter followers, our LinkedIn connections, the members of our Discord servers, or the community of a specific subreddit. Our lives are woven into complex digital networks that provide the perfect terrain for the principle of network reciprocity to operate—with all its benefits and drawbacks.

The internet is filled with positive examples of network reciprocity in action. Just think of:

- Open-source communities (e.g., Linux, Python): Thousands of programmers from around the world collaborate to build complex software for free. They form a closed, supportive network where cooperation and knowledge-sharing are the norms.

- Online support groups: Forums for people battling illnesses, grieving a loss, or raising young children are protected clusters where empathy and mutual aid are the guiding principles. Members shield one another from the judgment of the outside world.

- Wikipedia: A global network of editors works toward a common goal, maintaining strict internal norms and quality control to protect the project from vandalism (from the "defectors").

These communities are the "islands of kindness" in the digital space, capable of creating immense value under the protection of their network structure. The algorithms that connect people with similar interests often amplify this clustering effect, whether intentionally or not.

But this clustering mechanism, which so effectively protects cooperation, is a double-edged sword. Unfortunately, the principle itself is entirely neutral. The same principle that protects cooperation can also entrench misinformation and extremist ideologies. Modern research, especially in network science and computational social science, increasingly highlights this dark side of network structure:

- Echo Chambers: When people in a network interact almost exclusively with like-minded individuals, a closed informational cluster forms. Within this environment, existing beliefs are constantly reinforced, while opposing views—the "defector" information, from the system's perspective—are effectively filtered out.

- Polarization: Communication between two clusters holding opposing views can break down almost completely. Cooperation within the group (reinforcing each other's opinions) is maximized, while interaction between groups becomes hostile. The network structure thus contributes to deepening social divides.

This phenomenon explains why it can feel nearly impossible to persuade someone with facts in an online debate. You’re not just arguing with one person; you’re arguing against an entire, tightly-knit, self-protecting network cluster.

Conclusion: The Double-Edged Sword of Networks

Nowak and May’s insight from over 30 years ago remains fundamental. They showed that the fate of cooperation isn't decided in a single global battle but is the emergent result of countless local interactions. The structure of our connections—who we talk to and who we learn from—is just as important as the behavioral rules we follow.

In the digital age, this realization carries a dual message. Our networks can provide a sanctuary for cooperation, allowing supportive and creative communities to flourish. Yet, this same clustering force can also isolate us from one another, reinforcing our most harmful misconceptions. One of the greatest challenges of the 21st century is not just figuring out how to be cooperative within our own groups, but how to build bridges between these increasingly distant islands.